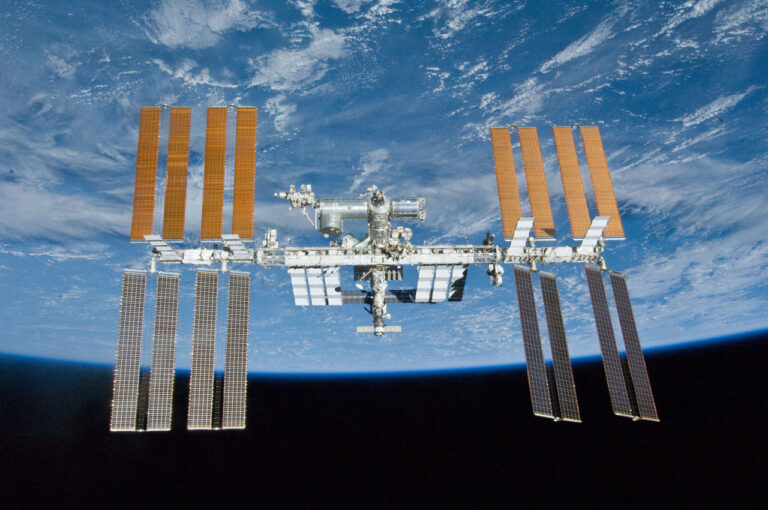

For the first time, mouse embryos have been successfully cultivated on the International Space Station (ISS) in a ground-breaking experiment.

Under the direction of Professor Teruhiko Wakayama of the University of Yamanashi in Japan, this ground-breaking study attempts to investigate the viability of human reproduction in space.

An article in New Scientist states that the study began with the removal of early two-cell stage embryos from pregnant mice. The embryos were then frozen and sent to the International Space Station (ISS) using a SpaceX rocket that was launched from Florida in August 2021.

The embryos were kept in specially made containers that made it simple for astronauts to defrost and cultivate them. The embryos were chemically preserved and sent back to Earth after four days.

Since embryos may only live outside of a uterus for this long, the four-day cultivation time was chosen. After returning to Earth, the scientists studied the embryos to see if the lower gravity and increased radiation in space, known as microgravity, had affected the embryos’ growth.

Despite their brief sojourn in space, the embryos did not exhibit any evidence of radiation-induced DNA damage, which was unexpected. Additionally, they showed signs of normal structural development, differentiating into the two cell groups that make up the placenta and fetus. This is especially important because it was thought that microgravity would prevent embryos from dividing into these two distinct cell types.

Studies on pregnant rats sent on NASA spaceflights suggest that normal development is conceivable, even though it is still unclear whether later phases of embryo development would be disturbed in space. When these rats returned to Earth, they gave birth to typical-weight pups, demonstrating that their gestation in space had gone according to plan.

Wakayama told New Scientist that “perhaps mammalian space reproduction is possible” in light of the findings. He did admit, though, that there are still unknowns around the actual full-term birth of a human baby or mouse pup in microgravity.

The next step for Wakayama’s team is to investigate if mouse embryos that were sent to the International Space Station (ISS) and later returned to Earth can implant in female mice and grow into healthy children.

This will shed further light on the survivability of embryos exposed to microgravity and radiation in space. Whether mouse sperm and eggs can be used for in-vitro fertilization (IVF) in space to generate embryos is another goal of the study team.

- Top 5 AI chatbots you need to try: ChatGPT, Google Bard, and more…

- Asteroid Hunters Spot a Potentially Dangerous ‘Planet Killer’ Hiding in the Sun’s Glare

- ‘Polymathic AI,’ a new ChatGPT-like AI tool for scientific discovery, has been launched

- Sony Spatial Reality Display allows you to enjoy 3D content without the use of glasses

1,709 comments

[…] Technology […]

Заработай права управления автомобилем в лучшей автошколе!

Стань профессиональной карьере автолюбителя с нашей автошколой!

Пройди обучение в лучшей автошколе города!

Задай тон правильного вождения с нашей автошколой!

Стремись к безупречным навыкам вождения с нашей автошколой!

Научись уверенно водить автомобиль с нами в автошколе!

Достигай независимости и свободы, получив права в автошколе!

Прояви мастерство вождения в нашей автошколе!

Открой новые возможности, получив права в автошколе!

Приведи друзей и они заработают скидку на обучение в автошколе!

Стань профессиональному будущему в автомобильном мире с нашей автошколой!

знакомства и научись водить автомобиль вместе с нашей автошколой!

Развивай свои навыки вождения вместе с профессионалами нашей автошколы!

Запиши обучение в автошколе и получи бесплатный консультационный урок от наших инструкторов!

Стремись к надежности и безопасности на дороге вместе с нашей автошколой!

Прокачай свои навыки вождения вместе с профессионалами в нашей автошколе!

Завоевывай дорожные правила и навыки вождения в нашей автошколе!

Стремись к настоящим мастером вождения с нашей автошколой!

Набери опыт вождения и получи права в нашей автошколе!

Пробей дорогу вместе с нами – пройди обучение в автошколе!

курси водіння київ троєщина https://avtoshkolaznit.kiev.ua/ .

Витонченість пін ап

казино з бонусами http://pinupcasinoqgcvbisd.kiev.ua/ .

Советы профессионалов по использованию ремонтной смеси

заказать смесь remontnaja-smes-dlja-kirpichnoj-kladki.ru .

Семейный отпуск без хлопот

– Автобусные туры в Турцию

все включено турция [url=https://www.anex-tour-turkey.ru/]https://www.anex-tour-turkey.ru/[/url] .

Горячее предложение: туры в Турцию

купить тур в турцию https://www.tez-tour-turkey.ru .

Быстрые грузоперевозки в Харькове

вывоз строительного мусора в харькове moving-company-kharkov.com.ua .

[url=https://www.yachtrentalsnirof.com]yachtrentalsnirof.com[/url]

A site to compare prices for renting yachts, sailboats, catamarans in every direction the world and rip your yacht cheaper.

http://www.yachtrentalsnirof.com

Великий вибір спецтехніки

спец машини https://spectehnika-sksteh.co.ua .

Подробное руководство

10. Установка кондиционера: детальное описание процесса

установка кондиционера цена https://ustanovit-kondicioner.ru/ .

Лучшие предложения по продаже кондиционеров

ремонт кондиціонера http://www.prodazha-kondicionera.ru .

1. Где купить кондиционер: лучшие магазины и выбор

2. Как выбрать кондиционер: советы по покупке

3. Кондиционеры в наличии: где купить прямо сейчас

4. Купить кондиционер онлайн: удобство и выгодные цены

5. Кондиционеры для дома: какой выбрать и где купить

6. Лучшие предложения на кондиционеры: акции и распродажи

7. Кондиционер купить: сравнение цен и моделей

8. Кондиционеры с установкой: где купить и как установить

9. Где купить кондиционер с доставкой: быстро и надежно

10. Кондиционеры: где купить качественный товар по выгодной цене

11. Кондиционер купить: как выбрать оптимальную мощность

12. Кондиционеры для офиса: какой выбрать и где купить

13. Кондиционер купить: самый выгодный вариант

14. Кондиционеры в рассрочку: где купить и как оформить

15. Кондиционеры: лучшие магазины и предложения

16. Кондиционеры на распродаже: где купить по выгодной цене

17. Как выбрать кондиционер: советы перед покупкой

18. Кондиционер купить: где найти лучшие цены

19. Лучшие магазины кондиционеров: где купить качественный товар

20. Кондиционер купить: выбор из лучших моделей

монтаж кондиционера kondicioner-cena.ru .

linetogel

linetogel

Impressive, congrats

Wonderful content

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

защита от ржавчины металла https://ingibitor-korrozii-msk.ru/ .

коляска для двойни https://www.detskie-koljaski-msk.ru .

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

Тепловизоры: современные технологии и возможности

купить тепловизоры https://teplovizor-od.co.ua/ .

Как увеличить посещаемость сайта: лучшие практики

3

продвижения сайта в гугле seo-prodvizhenie-sayta.co.ua .

wow, amazing

https://mtsn19jakartaselatan.sch.id/skuy/?daftar=JONITOGEL

https://sipp.pa-malili.go.id/?web=ziatogel

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

https://goldfrance.com

bliblibli

bluatblaaotuy

blablablu

blolbo

nice content!nice history!!

blibli

bliblibli

lalablublu

blolbo

lalablublu

palabraptu

blublun

cululutata

wow, amazing

lalablublu

lalablublu

Excellent write-up

SCAM

bliblibli

blobloblu

blobloblu

cululutata

LOSE MONEY

LOSE MONEY

wow, amazing

1SS3D249742

boba 😀

blibliblu

blublun

124969D742

cululutata

124SDS9742

bliloblo

1. Вибір натяжних стель – як правильно обрати?

2. Топ-5 популярних кольорів натяжних стель

3. Як зберегти чистоту натяжних стель?

4. Відгуки про натяжні стелі: плюси та мінуси

5. Як підібрати дизайн натяжних стель до інтер’єру?

6. Інноваційні технології у виробництві натяжних стель

7. Натяжні стелі з фотопечаттю – оригінальне рішення для кухні

8. Секрети вдалого монтажу натяжних стель

9. Як зекономити на встановленні натяжних стель?

10. Лампи для натяжних стель: які вибрати?

11. Відтінки синього для натяжних стель – ексклюзивний вибір

12. Якість матеріалів для натяжних стель: що обирати?

13. Крок за кроком: як самостійно встановити натяжні стелі

14. Натяжні стелі в дитячу кімнату: безпека та креативність

15. Як підтримувати тепло у приміщенні за допомогою натяжних стель

16. Вибір натяжних стель у ванну кімнату: практичні поради

17. Натяжні стелі зі структурним покриттям – тренд сучасного дизайну

18. Індивідуальність у кожному домашньому інтер’єрі: натяжні стелі з друком

19. Як обрати освітлення для натяжних стель: поради фахівця

20. Можливості дизайну натяжних стель: від класики до мінімалізму

натяжні стелі ціна з роботою https://natjazhnistelitvhyn.kiev.ua .

blibliblu

bliloblo

wow, amazing

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

blublu

blublun

cululutata

blolbo

boba 😀

hello

wow, amazing

palabraptu

bluatblaaotuy

blablablu

nice content!nice history!!

palabraptu

bliblibli

blolbo

1249742

bluatblaaotuy

blablablu

bliloblo

blolbo

bliblibli

blablablu

bliblibli

bluatblaaotuy

blobloblu

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

nice content!nice history!! boba 😀

bluatblaaotuy

blobloblu

124SDS9742

bliloblo

bluatblaaotuy

1. Вибір натяжних стель: як вибрати ідеальний варіант?

2. Модні тренди натяжних стель на поточний сезон

3. Які переваги мають натяжні стелі порівняно зі звичайними?

4. Як підібрати кольори для натяжної стелі у квартирі?

5. Секрети догляду за натяжними стелями: що потрібно знати?

6. Як зробити вибір між матовими та глянцевими натяжними стелями?

7. Натяжні стелі в інтер’єрі: як вони змінюють приміщення?

8. Натяжні стелі для ванної кімнати: плюси та мінуси

9. Як підняти стеля візуально за допомогою натяжної конструкції?

10. Як вибрати правильний дизайн натяжної стелі для кухні?

11. Інноваційні технології виробництва натяжних стель: що варто знати?

12. Чому натяжні стелі вибирають для офісних приміщень?

13. Натяжні стелі з фотопринтом: які переваги цієї технології?

14. Дизайнерські рішення для натяжних стель: ідеї для втілення

15. Хімічні реагенти в складі натяжних стель: безпека та якість

16. Як вибрати натяжну стелю для дитячої кімнати: поради батькам

17. Які можливості для дизайну приміщень відкривають натяжні стелі?

18. Як впливає вибір матеріалу на якість натяжної стелі?

19. Інструкція з монтажу натяжних стель власноруч: крок за кроком

20. Натяжні стелі як елемент екстер’єру будівлі: переваги та недоліки

ціна натяжних стель львів https://www.natjazhnistelifvgtg.lviv.ua .

blibli

nice content!nice history!!

palabraptu

124SDS9742

blublu

phising

blablablu

blobloblu

palabraptu

1249742

bliblibli

lost money

1249742

1SS3D249742

bluatblaaotuy

blobloblu

blobloblu

lost money

phising

phising

lost money

blablablu

bluatblaaotuy

boba 😀

bliloblo

1SS3D249742

lost money

lost money

phising

Thaqnk you for every other great article. The place else could anyone get tha type of info in such an ideal method of writing?

I have a presentation subsequent week, and I’m at thhe search

for suc information.

My blog post … 링크모음

scam

great article

lost money

blublu

124SDS9742

blabla

купить алюминиевый выбор плинтуса .

124969D742

blibli

1. Как выбрать идеальный гипсокартон для ремонта

сетка металлическая купить лист гкл .

blublun

blibli

коляски детские коляска купить .

I highly advise stay away from this site. The experience I had with it has been nothing but disappointment as well as concerns regarding scamming practices. Exercise extreme caution, or even better, seek out a more reputable site to meet your needs.

THIS IS SCAM

LOSE MONEY

nice content!nice history!!

LOSE MONEY

I highly advise steer clear of this platform. My own encounter with it has been purely disappointment and doubts about scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, seek out an honest service for your needs.

I highly advise steer clear of this site. My own encounter with it was only disappointment along with doubts about scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, seek out an honest platform to fulfill your requirements.

I strongly recommend to avoid this platform. My own encounter with it was only frustration and concerns regarding deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or better yet, find a trustworthy platform to fulfill your requirements.

SCAM

blabla

PISHING

THIS IS SCAM

blibli

blibli

I strongly recommend stay away from this site. My personal experience with it has been only frustration and concerns regarding deceptive behavior. Be extremely cautious, or alternatively, find a more reputable site for your needs.

I strongly recommend stay away from this site. The experience I had with it was purely frustration as well as doubts about scamming practices. Exercise extreme caution, or alternatively, look for an honest platform to fulfill your requirements.

1249742

blublun

I urge you stay away from this site. My personal experience with it was purely dismay along with concerns regarding deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or better yet, find an honest platform to meet your needs.

THIS IS SCAM

I strongly recommend steer clear of this platform. The experience I had with it was nothing but frustration and doubts about deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, look for an honest service to meet your needs.

nice content!nice history!!

I highly advise steer clear of this platform. My personal experience with it has been purely disappointment and doubts about deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, find an honest platform to fulfill your requirements.

I highly advise steer clear of this site. My personal experience with it was purely dismay and concerns regarding fraudulent activities. Be extremely cautious, or alternatively, seek out an honest site for your needs.

124969D742

palabraptu

124SDS9742

blabla

blublun

124SDS9742

blabla

blublu

I highly advise stay away from this site. My own encounter with it was only disappointment along with suspicion of deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, look for a trustworthy site to meet your needs.

I urge you steer clear of this platform. My personal experience with it was only frustration and concerns regarding scamming practices. Exercise extreme caution, or alternatively, look for a more reputable service to meet your needs.

lalablublu

1SS3D249742

Найліпший вибір для пригодницького духу

Збереження безпеки

тактичні рюкзаки https://ryukzakivijskovibpjgl.kiev.ua/ .

1SS3D249742

I urge you stay away from this platform. My personal experience with it was purely frustration as well as suspicion of scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or better yet, find a trustworthy site to fulfill your requirements.

blolbo

blibli

blibliblu

124SDS9742

blublu

lalablublu

blibliblu

bliloblo

blolbo

Воєнторг

6. Тактические рюкзаки и сумки для военных

тактичні рукавиці літні тактичні рукавиці літні .

1. Вибір натяжної стелі: як правильно підібрати?

2. ТОП-5 переваг натяжних стель для вашого інтер’єру

3. Як доглядати за натяжною стелею: корисні поради

4. Натяжні стелі: модний тренд сучасного дизайну

5. Як вибрати кольорову гаму для натяжної стелі?

6. Натяжні стелі від А до Я: основні поняття

7. Комфорт та елегантність: переваги натяжних стель

8. Якість матеріалів для натяжних стель: що обрати?

9. Ефективне освітлення з натяжними стелями: ідеї та поради

10. Натяжні стелі у ванній кімнаті: плюси та мінуси

11. Як відремонтувати натяжну стелю вдома: поетапна інструкція

12. Візуальні ефекти з допомогою натяжних стель: ідеї дизайну

13. Натяжні стелі з фотопринтом: оригінальний дизайн для вашого інтер’єру

14. Готові або індивідуальні: які натяжні стелі обрати?

15. Натяжні стелі у спальні: як створити атмосферу затишку

16. Вигода та функціональність: чому варто встановити натяжну стелю?

17. Натяжні стелі у кухні: практичність та естетика поєднуються

18. Різновиди кріплень для натяжних стель: який обрати?

19. Комплектація натяжних стель: що потрібно знати при виборі

20. Натяжні стелі зі звукоізоляцією: комфорт та тиша у вашому будинку!

потолки натяжні https://natyazhnistelidfvf.kiev.ua/ .

1SS3D249742

Magnificent website. Plenty of useful info here. I am sending it to some friends ans also sharing in delicious. And obviously, thank you for your sweat!

I urge you stay away from this platform. My personal experience with it was nothing but disappointment as well as concerns regarding scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or better yet, find a trustworthy site to fulfill your requirements.I highly advise to avoid this site. The experience I had with it has been purely disappointment along with doubts about fraudulent activities. Be extremely cautious, or alternatively, find a trustworthy service for your needs.

I strongly recommend stay away from this platform. My own encounter with it has been purely dismay and doubts about fraudulent activities. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, seek out a trustworthy site for your needs.I urge you stay away from this site. The experience I had with it has been purely frustration as well as suspicion of fraudulent activities. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, look for an honest service to fulfill your requirements.

bliloblo

blabla

124969D742

cululutata

blublun

palabraptu

blublu

blibli

palabraptu

1249742

blublu

I just like the helpful info you provide on your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and check once more right here frequently. I am quite sure I will be told a lot of new stuff proper here! Best of luck for the next!

naturally like your web-site but you have to check the spelling on quite a few of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to tell the reality then again I will certainly come again again.

Would you be excited about exchanging links?

nice content!nice history!!

blibli

bliloblo

blibliblu

cululutata

blibli

I urge you to avoid this platform. My personal experience with it has been only frustration and concerns regarding fraudulent activities. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, look for an honest platform to meet your needs.

1SS3D249742

124969D742

blabla

lalablublu

boba 😀

1SS3D249742

blolbo

I urge you stay away from this platform. My own encounter with it was purely frustration as well as doubts about deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, seek out a trustworthy site for your needs.

1SS3D249742

124969D742

nice content!nice history!!

blublun

1SS3D249742

1SS3D249742

blibli

palabraptu

Thank you for the good writeup. It in reality was a leisure account it. Glance complicated to more brought agreeable from you! By the way, how can we keep in touch?

124969D742

blibliblu

124969D742

I strongly recommend to avoid this platform. My own encounter with it has been purely disappointment as well as concerns regarding fraudulent activities. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, find a trustworthy service to meet your needs.

1SS3D249742

lalablublu

124SDS9742

lalablublu

blibliblu

I strongly recommend to avoid this platform. My own encounter with it has been purely dismay as well as concerns regarding scamming practices. Be extremely cautious, or better yet, look for a trustworthy platform to fulfill your requirements.

blublu

blabla

Woah! I’m really digging the template/theme of this blog. It’s simple, yet effective. A lot of times it’s very hard to get that “perfect balance” between usability and appearance. I must say that you’ve done a excellent job with this. Also, the blog loads very quick for me on Firefox. Excellent Blog!

124969D742

lalablublu

Balmorex Pro is a natural and amazing pain relief formula that decreases joint pain and provides nerve compression relief.

bliloblo

What is Lottery Defeater Software? Lottery software is a specialized software designed to predict and facilitate individuals in winning lotteries.

I urge you stay away from this platform. My personal experience with it has been only frustration as well as suspicion of deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, find a trustworthy platform to meet your needs.

cululutata

lalablublu

Dentitox Pro is marketed as a natural oral health supplement designed to support dental health and hygiene.

124969D742

124969D742

I every time spent my half an hour to read this webpage’s articles all the time along with

a cup of coffee.

I used to be very pleased to seek out this internet-site.I wanted to thanks on your time for this glorious read!! I undoubtedly having fun with each little bit of it and I have you bookmarked to check out new stuff you weblog post.

lalablublu

Outstanding quest there. What occurred after?

Take care!

lalablublu

I highly advise to avoid this site. My own encounter with it has been only dismay along with concerns regarding scamming practices. Exercise extreme caution, or even better, find an honest service for your needs.

blublun

lalablublu

lalablublu

blolbo

1SS3D249742

1249742

cululutata

I strongly recommend stay away from this site. The experience I had with it has been nothing but disappointment along with doubts about deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, look for a trustworthy service for your needs.

Hello I am so excited I found your webpage, I really found you by accident, while I was looking on Bing

for something else, Anyhow I am here now and would just like to say cheers for a tremendous post

and a all round enjoyable blog (I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to read

through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also added in your RSS feeds,

so when I have time I will be back to read a lot more, Please do keep up the great

jo.

blublun

palabraptu

I don’t know whether it’s just me or if

perhaps everyone else experiencing issues with your blog.

It seems like some of the written text on your posts are running off the screen.

Can someone else please provide feedback and let me know if this is happening to

them too? This might be a issue with my browser because I’ve had this happen previously.

Thank you

I urge you to avoid this platform. My personal experience with it was only dismay and concerns regarding fraudulent activities. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, find a trustworthy service to fulfill your requirements.

I for all time emailed this weblog post page to all my associates, since if like to

read it then my friends will too.

blublu

I highly advise steer clear of this platform. The experience I had with it was only dismay as well as concerns regarding fraudulent activities. Exercise extreme caution, or even better, seek out a more reputable platform to fulfill your requirements.

1SS3D249742

blibliblu

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your content seem to be running off the screen in Chrome. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Thanks

Hi, Neat post. There is an issue along with your website in internet explorer, may check this?

IE nonetheless is the marketplace chief and a large component of

people will omit your great writing because of this problem.

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude! Thank you, However I am experiencing issues with your RSS.

I don’t understand the reason why I can’t subscribe to it.

Is there anybody else getting identical RSS problems? Anybody who knows the solution will you kindly

respond? Thanks!!

I urge you stay away from this platform. My own encounter with it was nothing but dismay along with doubts about scamming practices. Be extremely cautious, or even better, look for an honest site to fulfill your requirements.

I cling on to listening to the rumor lecture about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the best site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i find some?

1249742

blibliblu

I visited multiple sites except the audio quality for audio songs current at this

website is really excellent.

blublu

1249742

http://202.152.150.220

blublu

Greetings! This is my 1st comment here so I just wanted to give a quick shout out and say I genuinely enjoy reading through your blog posts. Can you recommend any other blogs/websites/forums that deal with the same subjects? Thanks for your time!

nice content!nice history!!

I strongly recommend stay away from this site. My personal experience with it has been purely disappointment along with concerns regarding scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or better yet, seek out a more reputable service for your needs.

boba 😀

blolbo

Great blog here! Also your web site loads up fast! What host are you using? Can I get your affiliate link to your host? I wish my site loaded up as quickly as yours lol

Howdy! I could have sworn I’ve been to your blog before but after going through some of the articles I realized it’s new to me.

Anyways, I’m certainly delighted I stumbled upon it and I’ll be book-marking it and checking back regularly!

I urge you to avoid this platform. My personal experience with it has been only dismay along with doubts about scamming practices. Be extremely cautious, or even better, find an honest platform to meet your needs.

It is perfect time to make some plans for the longer term and it’s time to

be happy. I have learn this submit and if I may just I desire

to suggest you few interesting issues or suggestions.

Perhaps you could write next articles regarding this article.

I wish to learn more things approximately it!

blabla

1249742

I like the helpful information you provide for your

articles. I will bookmark your weblog and check again right here frequently.

I am rather sure I’ll learn plenty of new stuff proper here!

Good luck for the next!

Thank you for sharing your info. I truly appreciate your efforts and I am waiting for your further write ups thank

you once again.

Hi, I do think this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it

😉 I am going to come back yet again since I bookmarked it.

Money and freedom is the greatest way to change, may

you be rich and continue to guide other people.

blublu

boba 😀

Simply desire to say your article is as astounding.

The clarity in your post is simply cool and i can assume you are

an expert on this subject. Fine with your permission allow me to grab your

RSS feed to keep updated with forthcoming post.

Thanks a million and please keep up the gratifying work.

Inspiring story there. What occurred after? Thanks!

I truly love your site.. Great colors & theme. Did

you build this amazing site yourself? Please reply back as

I’m trying to create my own personal blog and would

love to learn where you got this from or just what the theme is named.

Kudos!

I have learn some just right stuff here. Definitely price bookmarking

for revisiting. I wonder how much attempt

you set to create this type of fantastic informative website.

It’s an amazing paragraph for all the internet users; they will take benefit from it I

am sure.

Hmm is anyone else encountering problems with the pictures on this

blog loading? I’m trying to find out if its a problem

on my end or if it’s the blog. Any feed-back would be greatly appreciated.

Hello would you mind letting me know which webhost you’re utilizing?

I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different internet browsers and

I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most. Can you recommend a good internet hosting provider at a fair price?

Kudos, I appreciate it!

My partner and I stumbled over here different web page and

thought I should check things out. I like what I see so now

i am following you. Look forward to checking out your web page repeatedly.

There’s noticeably a bundle to know about this. I assume you made sure nice factors in options also.

Heya i’m for the primary time here. I found this board and

I to find It truly helpful & it helped me out much.

I’m hoping to offer one thing back and aid others

such as you helped me.

When some one searches for his required thing, thus he/she wants to be available that in detail, therefore that thing is maintained over here.

It’s difficult to find well-informed people about this subject, but you seem like you know what you’re talking about!

Thanks

blabla

lalablublu

Wow, superb weblog structure! How lengthy have you ever been running a blog for?

you made blogging glance easy. The entire look of your website is wonderful,

let alone the content material!

I highly advise to avoid this site. My own encounter with it has been purely frustration along with concerns regarding deceptive behavior. Proceed with extreme caution, or alternatively, look for a trustworthy platform for your needs.

bliloblo

I like what you guys are up too. This type of clever work and reporting!

Keep up the great works guys I’ve included you guys to our blogroll.

blibliblu

I haven’t checked in here for a while since I thought it was getting boring, but the last few posts are good quality so I guess I’ll add you back to my everyday bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

I highly advise stay away from this site. My own encounter with it was purely frustration and concerns regarding scamming practices. Proceed with extreme caution, or even better, find an honest service for your needs.

1249742

Hey would you mind letting me know which web host you’re using?

I’ve loaded your blog in 3 different web browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot quicker then most.

Can you suggest a good hosting provider at a reasonable price?

Kudos, I appreciate it!

Every weekend i used to visit this web page, because i want enjoyment, for the reason that this this web site conations genuinely

fastidious funny data too.

I blog quite often and I really appreciate your content. This

great article has really peaked my interest.

I am going to take a note of your website and keep checking for new details about once per week.

I subscribed to your Feed too.

Hey there! I simply would like to give you a big thumbs up for your great information you have got here on this

post. I am returning to your site for more soon.

palabraptu

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here.

The sketch is tasteful, your authored subject matter stylish.

nonetheless, you command get got an edginess over that

you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably

come more formerly again as exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this increase.

I was curious if you ever considered changing the page layout of your

site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say.

But maybe you could a little more in the way of content

so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of

text for only having 1 or two images. Maybe you could space it out better?

1SS3D249742

blibli

An intriguing discussion is worth comment.

I think that you should write more about this issue, it might

not be a taboo matter but typically people do

not discuss such topics. To the next! Kind regards!!

Just desire to say your article is as astonishing. The clarity to your post

is just great and that i could think you’re a professional in this subject.

Fine with your permission let me to grab your feed to keep up

to date with coming near near post. Thank you one million and please

keep up the enjoyable work.

Do you have a spam issue on this website; I also am

a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; many of us have created some nice practices and we are looking to swap solutions with other

folks, why not shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Hey there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words in your content seem

to be running off the screen in Firefox. I’m not sure if this

is a format issue or something to do with browser compatibility but I thought

I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though!

Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Cheers

It’s really a great and useful piece of info. I

am satisfied that you simply shared this useful information with us.

Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Hello there! Do you know if they make any plugins to safeguard against hackers?

I’m kinda paranoid about losing everything I’ve worked hard on. Any

suggestions?

Can I just say what a comfort to discover someone

that actually understands what they are discussing over the internet.

You certainly understand how to bring a problem to light and make it important.

A lot more people have to check this out and understand this side of

the story. I was surprised you aren’t more popular given that you definitely have the gift.

I savor, lead to I discovered just what I was having a look for.

You have ended my 4 day long hunt! God Bless you man. Have a great day.

Bye

I’m extremely pleased to discover this page. I need to to thank you for ones time for this particularly wonderful read!!

I definitely appreciated every bit of it and I have you saved as a favorite to check out new information in your site.

My family always say that I am killing my time here at net, except I know I am getting experience everyday

by reading thes nice content.

Very soon this web site will be famous amid all blogging and site-building people, due to it’s pleasant articles or reviews

Hello, its good paragraph regarding media print,

we all understand media is a great source of data.

I think the admin of this site is actually working hard

in favor of his web site, since here every material is quality

based data.

Thanks for sharing your info. I truly appreciate

your efforts and I will be waiting for your next post thanks once again.

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d certainly donate to

this excellent blog! I suppose for now i’ll settle for bookmarking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account.

I look forward to brand new updates and will share this blog with my Facebook group.

Chat soon!

Hi, Neat post. There is an issue along with your website

in web explorer, could check this? IE nonetheless is the marketplace chief and a good part of other

people will omit your wonderful writing due to this

problem.

Awesome! Its genuinely amazing post, I have got much clear idea about from this post.

We’re a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your website offered us with valuable info to work on. You have

done a formidable job and our entire community will be thankful to you.

Hello, you used to write magnificent, but the last few posts have been kinda boring… I miss your tremendous writings. Past few posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!

I think this is among the most vital info for me.

And i’m glad reading your article. But want to remark on few general things, The site

style is ideal, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers

Wow, incredible weblog format! How lengthy have you been running a blog for?

you made blogging glance easy. The entire glance of your site is fantastic, let alone the content!

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my weblog

thus i came to “return the favor”.I’m trying to find things

to improve my site!I suppose its ok to use a few

of your ideas!!

Greetings from Colorado! I’m bored to tears at work so I decided to check out your blog on my iphone

during lunch break. I love the info you provide here and can’t wait to take a look when I get

home. I’m surprised at how fast your blog loaded on my mobile ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, fantastic site!

This piece of writing provides clear idea in favor of the new visitors of blogging, that in fact how to do blogging.

After I originally commented I appear to have

clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is

added I recieve four emails with the exact same comment.

Is there a means you are able to remove me from that service?

Thanks!

I’m really impressed with your writing skills and also with the layout on your weblog.

Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Either

way keep up the nice quality writing, it’s rare to see a great blog

like this one nowadays.

Hey there I am so thrilled I found your weblog, I really found you by error, while I was looking on Askjeeve

for something else, Nonetheless I am here now and would just like to say many thanks for a remarkable post

and a all round thrilling blog (I also love the theme/design),

I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have

bookmarked it and also added your RSS feeds, so when I have time I will be back to read much more, Please

do keep up the great b.

Fantastic post but I was wondering if you could

write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit more.

Bless you!

I visited multiple blogs however the audio quality for audio songs current at this site is in fact excellent.

No matter if some one searches for his required thing, therefore he/she needs

to be available that in detail, thus that thing is maintained

over here.

Теневой плинтус: стильное решение для обновления интерьера,

Как правильно установить теневой плинтус своими руками,

Креативные способы использования теневого плинтуса в дизайне помещения,

Ретро-стиль с использованием теневых плинтусов: идеи для вдохновения,

Гармония оттенков: выбор цвета теневого плинтуса для любого интерьера,

Как спрятать коммуникации с помощью теневого плинтуса: практические советы,

Теневой плинтус с подсветкой: создаем эффектное освещение в интерьере,

Современные тренды в использовании теневого плинтуса для уюта и красоты,

Теневой плинтус: деталь, которая делает интерьер законченным и гармоничным

плинтус теневой https://plintus-tenevoj-aljuminievyj-msk.ru/ .

blabla

blibliblu

1249742

Way cool! Some very valid points! I appreciate you penning this article and the rest of the site is also really good.

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this post plus

the rest of the website is very good.

Terrific article! This is the type of information that should be

shared across the net. Disgrace on Google for no longer positioning this put up higher!

Come on over and visit my web site . Thanks =)

Ahaa, its pleasant dialogue regarding this piece of writing here at this weblog, I have read

all that, so at this time me also commenting at this place.

Hi there everyone, it’s my first pay a visit at this web page, and post is actually fruitful designed for

me, keep up posting such articles.

blublu

Hello There. I discovered your weblog the use of

msn. This is a very neatly written article. I’ll be sure to bookmark it

and come back to read more of your useful information. Thank you

for the post. I will certainly comeback.

Touche. Solid arguments. Keep up the great work.

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your

content seem to be running off the screen in Firefox.

I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to

do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post to

let you know. The design and style look great though! Hope you get the problem solved soon. Kudos

My relatives every time say that I am killing my time here at web, however I know I am getting

experience all the time by reading such pleasant content.

palabraptu

Thanks for the marvelous posting! I certainly enjoyed reading it, you can be a great author.I will ensure that I bookmark your blog and definitely will come back

later in life. I want to encourage one to continue your great writing, have

a nice afternoon!

Hi, I do think this is a great web site. I stumbledupon it

😉 I am going to return once again since i have book

marked it. Money and freedom is the greatest way to change,

may you be rich and continue to help other people.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is a very well written article.

I’ll be sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful

info. Thanks for the post. I’ll certainly return.

Link exchange is nothing elsee except it is only placing the other person’s web site link on your page at suitable

place and other person will also do same

in favor of you.

My web page; air conditioning

Danger: This site is a scam, report it

You are my intake, I own few web logs and occasionally run out from to post .

I was recommended this blog by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post

is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about

my problem. You are amazing! Thanks!

I’d like to thank you for the efforts you’ve

put in penning this blog. I am hoping to view the same

high-grade blog posts by you later on as well.

In truth, your creative writing abilities has motivated

me to get my own site now 😉

Stay vigilant: Beware, this website is fraudulent, report it

FitSpresso is a natural weight loss supplement crafted from organic ingredients, offering a safe and side effect-free solution for reducing body weight.

Usually I do not read post on blogs, however I would like

to say that this write-up very pressured me to try

and do it! Your writing style has been amazed me. Thank you, quite great post.

First off I want to say awesome blog! I had a quick question in which I’d like to ask

if you don’t mind. I was curious to know how you

center yourself and clear your head before writing.

I’ve had difficulty clearing my mind in getting my thoughts out.

I truly do take pleasure in writing but it just seems like the

first 10 to 15 minutes are usually wasted just trying to

figure out how to begin. Any ideas or hints? Appreciate it!

Отличный сайт!!! Случайно

нашел его в Google и очень обрадовался!

Статьи, которые я прочитал здесь, оказались

информативными и очень практичными.

Большое спасибо за такой качественный, увлекательный контент.

Я, кстати, тоже создаю статьи на различные темы, но в основном про оптимизацию веб-сайтов и

контекстную рекламу Google https://www.multichain.com/qa/user/alexseo369 Если вам будет любопытно,

заходите на мой сайт, пообщаемся!

child porn

Hi I am so happy I found your website, I really found you by accident, while

I was looking on Aol for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to

say thanks a lot for a remarkable post and a all round entertaining blog

(I also love the theme/design), I don’t have time to browse it all at the minute but

I have book-marked it and also included your RSS feeds,

so when I have time I will be back to read

a great deal more, Please do keep up the excellent jo.

What a stuff of un-ambiguity and preserveness of precious familiarity regarding unexpected emotions.

What’s Happening i am new to this, I stumbled upon this I have

discovered It absolutely useful and it has helped me out loads.

I am hoping to contribute & assist other users

like its helped me. Great job.

Amaranthine Rose Preserved Roses Flower Delivery

Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Same Day

eternal flower

What i do not realize is if truth be told how you’re now not actually a lot more well-preferred than you might be right now. You’re very intelligent. You recognize therefore significantly with regards to this topic, produced me in my opinion consider it from so many various angles. Its like women and men aren’t interested until it¦s one thing to accomplish with Girl gaga! Your own stuffs excellent. Always deal with it up!

blibli

I got this web page from my buddy who told me regarding this site and

now this time I am visiting this web site and reading very

informative content at this time.

Absolutely indited content material, Really enjoyed examining.

Hello this is somewhat of off topic but I was wanting to know if blogs use WYSIWYG editors or if you have to manually code with HTML. I’m starting a blog soon but have no coding knowledge so I wanted to get guidance from someone with experience. Any help would be greatly appreciated!

https://www.datingsitesreviews.com/forum/viewtopic.php?showtopic=8185

blublu

124SDS9742

I think this is one of the most important info for me.

And i’m glad reading your article. But should remark on few general

things, The web site style is wonderful, the articles is

really nice : D. Good job, cheers

Выбор современных мужчин – тактичные штаны, дадут комфорт и уверенность.

Незаменимые для занятий спортом, тактичные штаны станут вашим надежным помощником.

Качественные материалы и прочные швы, сделают тактичные штаны вашим незаменимым спутником.

Максимальный комфорт и стильный вид, подчеркнут вашу индивидуальность и статус.

Почувствуйте удобство и стиль в тактичных штанах, которые подчеркнут вашу силу и уверенность.

зимові тактичні штани [url=https://taktichmishtanu.kiev.ua/]https://taktichmishtanu.kiev.ua/[/url] .

Great blog right here! Also your website loads up fast!

What web host are you the usage of? Can I am getting your

affiliate link on your host? I desire my web site loaded up

as fast as yours lol

Removals Blackpool by Cookson & Son Moving

Removals In Blackpool Made Easier

Are you looking for a friendly, reliable and affordable removals company near you?

Cookson and Sons offer a high quality service that specialises in removals in Blackpool, Preston, Wrea Green, Garstang, Kirkham and Lytham.

Moving house can be stressful and exhausting. With us you can organise your

storage and removal service right now. Contact us today to

make an enquiry.

Whats up very cool website!! Guy .. Beautiful .. Superb .. I will bookmark your website and take the feeds additionally?KI am happy to find numerous helpful information here within the put up, we’d like work out extra strategies in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Thanks to my father who informed me regarding this web site, this weblog is actually awesome.

It’s very trouble-free to find out any matter on web as compared to textbooks, as I found this post

at this web site.

Bandar Judi Kijang Toto termasuk situs judi togel online yang berani memberikan hadiah 4D yaitu 10 Juta Rupiah, kemudian 3D yaitu 1 Juta, dan juga 2D

sebesar 100ribu. Kijang Toto telah menjadi agen togel yang diminati

banyak pemain togel indonesia. Terbukti dari kualitas dan besarnya hadiah yang berani diberikan oleh Agen SGP terpercaya.

Good answers in return of this issue with solid arguments and describing all on the topic of that.

I absolutely love your blog.. Great colors & theme. Did you

develop this site yourself? Please reply back as I’m planning to create my

own personal website and would love to find out where you got this from or just

what the theme is called. Appreciate it!

Welcome to Tyler Wagner: Allstate Insurance, your premier insurance agency located in Las Vegas,

NV. Boasting extensive expertise in the insurance

industry, Tyler Wagner and his team are dedicated to

offering top-notch customer service and tailored insurance

solutions.

Whether you’re looking for auto insurance to home insurance, to life and

business insurance, Tyler Wagner: Allstate Insurance has your

back. Our wide range of coverage options guarantees that

you can find the perfect policy to meet your needs.

Understanding the importance of risk assessment, our team works diligently to offer custom

insurance quotes that are tailored to your specific needs.

By leveraging our expertise in the insurance market and state-of-the-art underwriting processes, Tyler Wagner ensures that you receive the most competitive premium calculations.

Dealing with insurance claims can be challenging, but with Tyler Wagner: Allstate Insurance

by your side, you’ll have a smooth process. Our efficient claims

processing system and dedicated customer service team make sure that your claims

are processed efficiently and with the utmost care.

Moreover, we are deeply knowledgeable about insurance law and regulation, ensuring that your coverage is consistently in compliance with

current legal standards. This expertise provides an added layer of security

to our policyholders, knowing that their insurance is robust and reliable.

At Tyler Wagner: Allstate Insurance, we believe that a good insurance policy is a key part of financial planning.

It’s an essential aspect for safeguarding your future and ensuring the well-being of your loved ones.

Therefore, our team make it our mission to understand

your individual needs and help you navigate through the choice among insurance options, making

sure that you have all the information you need and confident in your decisions.

Selecting Tyler Wagner: Allstate Insurance means choosing a trusted insurance broker in Las Vegas,

NV, who values relationships and excellence. We’re not just your insurance agents; we’re here to support you in creating a protected future.

Don’t wait to reach out today and discover how Tyler Wagner:

Allstate Insurance can transform your insurance experience in Las

Vegas, NV. Let us show you the difference of

working with an insurance agency that genuinely cares

about you and is dedicated to securing your peace of mind.

My spouse and I stumbled over here different web address and thought I might as well check things out.

I like what I see so now i’m following you. Look forward to

looking into your web page yet again.

I am really grateful to the owner of this website who has shared this wonderful post

at at this time.

My web-site: Puff Wow

I’d like to find out more? I’d care to find out more details.

However, the ethical implications of bulk DMT purchases cannot be overlooked.

I am glad to be one of several visitors on this great site (:, appreciate it for posting.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

Keep this going please, great job!

What Is Neotonics? Neotonics is a skin and gut health supplement that will help with improving your gut microbiome to achieve better skin and gut health.

Does your blog have a contact page? I’m having trouble

locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an e-mail. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it

expand over time.

What’s Happening i’m new to this, I stumbled upon this I’ve found

It positively useful and it has aided me out loads. I hope to contribute & assist different customers

like its helped me. Great job.

https://www.datingwise.com/review/flirt.com/

Flirt.com is for adults looking for fun, flirty encounters rather than serious dating. The site is aimed at the younger crowd, though there are older members there and some seeking longer term relationships. It offers free membership for women, while men can join for free but must pay for additional services such as email.

Flirt has been recently revamped and is designed for people looking for casual dating. Most people there are in their twenties and early thirties, though there is no upper age limit. It’s owned by the Cupid Dating network and caters mostly to members in the UK, the U.S. and Australia, though membership is open to anyone.

Flirt is “spicier” than your regular dating site – don’t expect to find your next significant other there.

Naughty mode

This site is designed to have a light, fun feel to it. It is not intended to be an “adult” site, though there is some mature content. Most adult content can be blocked by switching-off “naughty mode” (the initial setting).

This will hide any images that are explicit. Flirt is a worth a look if you are single and looking to meet new people and have a little fun. Those looking for more serious relationships would probably be better off looking elsewhere.

Features

Flirt.com is feature rich, offering email, message boards, chat rooms, member diaries, videos as well as basic flirts and emails. Flirt has a dedicated mobile site for those wanting access their matches on the go. They also sponsor speed dating and other live events for those who want to meet someone in person.

Membership

Women have access to all features of for free. Men can join for free, but will need a paid membership in order to use some features of the site. Despite being free for women there is still a very high proportion of male users.

Flirt ist ok. A few fake profiles (like everywhere), a few cam girls (like everywhere) and a few scammers (like everywhere) but generally the site seems to be real. Personally prefer because i’ve actually hooked up twice using it, but just wanted to try somethin’ new so decided to give Flirt a chance.

Avatar

topiJuly 11th, 2017

Useless

Not worth it. I had no luck on this site after six months.

Avatar

freedFebruary 8th, 2017

Just average

how do i join?

Avatar

ChrisOilSeptember 12th, 2016

Recommended

Though it’s a casual site, I met my love here. So everything’s in your hands. Try, you won’t lose anything.

Avatar

Paul87July 18th, 2016

Above average

Good site for flirting and one night stands! Unfortunately one day this won’t be enough for you and flirt cannot offer you something serious.

Avatar

Craig8686904June 21st, 2016

Recommended

I’m really glad that a friend of mine gave me the advice to register on Flirt to make my life more spicy. I wasn’t really going to have anything more than just a naughty chat but it turned out that there’s a nice lady in mt city who’s willing to date with me. I’m freaking happy now

Avatar

Chris53June 13th, 2016

Recommended

Though it’s a casual site, I met my love here. So everything’s in your hands. Try, you won’t lose anything.

Avatar

RobertGreen84June 8th, 2016

Above averag

Cute looking site like many others however only here I’ve had 5 dates within 3 weeks after the start. Also I should note that flirt sometimes really hard to use and it’s taking some time to feel yourself comfortable during usage of it and actually it’s not because of gliches or something simply the pictures of buttons are obvious so sometimes you can find yourself on the page you haven’t wanted to open. However I should admit that in the end it worth all the troubles in the start.

Avatar

JohnMApril 13th, 201

Avoid

This site is bull****, it’s a total scam, the profiles of women are not even real they are all fake, when you create a profile and it becomes active they suck you in by sending you lots of messages and winks from so called women which are not even real and don’t actually exist and because you can’t read the messages as an unpaid member to be able to read the messages you have to subscribe and pay for a membership then once you do that and you respond to the messages you don’t get a reply back.

It’s a con, warning to other people out there do not join this site.

Avatar

Michael_4302January 15th, 201

Useless

This site claims that singles are in your area, but in truth that they live elsewhere. I had received a lot of mail from people that the site claimed were in my area, but they actually lived far away. Beware of scammers as well, I have found quite a bit of them on this whose profiles seemed to be processed quickly since their information is available. However, those members who may actually be real usually have the contents of their profile information pending. I’ve seen a lot of scam activity on this site and very little actual people.

These are really wonderful ideas in regarding blogging. You have touched some fastidious things here.

Any way keep up wrinting.

What’s up i am kavin, its my first occasion to commenting anyplace, when i read this article i thought

i could also make comment due to this sensible post.

my blog does pickles make you fat

безопасно,

Лучшие стоматологи города, для вашего уверенного улыбки,

Современные методы стоматологии, для вашей улыбки,

Индивидуальный подход к каждому пациенту, для вашего комфорта и уверенности,

Эффективное лечение зубов и десен, для вашего здоровья и красоты улыбки,

Экстренная помощь в любое время суток, для вашего комфорта и удовлетворения,

Индивидуальный план лечения для каждого пациента, для вашего комфорта и удовлетворения

лікування зубів дітям https://stomatologichnaklinikafghy.ivano-frankivsk.ua/ .

Genuinely no matter if someone doesn’t know after that its up to other users that they

will assist, so here it occurs.

Excellent article et très informatif! Les services de construction en ligne offrent une

commodité incroyable pour les clients. Merci pour le partage de cet article et pour les conseils pratiques!

What a information of un-ambiguity and preserveness of valuable know-how

on the topic of unpredicted emotions.

An outstanding share! I have just forwarded this onto a colleague who has been conducting a little homework on this.

And he actually bought me dinner because I

found it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU

for the meal!! But yeah, thanks for spending the time to discuss this issue here on your

site.

Excellent post! We are linking to this great post on our website.

Keep up the great writing.

Hi there, yeah this post is genuinely nice and I have learned lot of things

from it concerning blogging. thanks.

120 Flirt com Reviews | flirt.com @ PissedConsumer

Flirt com has 120 reviews (average rating 1.1). Consumers say: Unauthorized money taken out of my account, It’s a $1.99 for one day drive I paid it you all took $5.99 out of my account two times and then took a extra $23.31 out of my account this is outrageous I did not ask for that I want my money… Flirt com has 1.1 star rating based on 41 customer reviews. Consumers are mostly dissatisfied Rating Distribution 95% negative 2% positive Pros: Everyone is fake, I have no idea, I-o nu folosesc. Cons: Scamming, All fake profile there, All kind. Recent recommendations regarding this business are as follows: “Don’t activate anything on this fake, fony and complicated site app.”, “Nothing to recommend at this stage”, “Do not use this site”, “Don’t pay for this scam it’s a SCAM”, “Do not have any type of business with this fraudulent company”. Most users ask Flirt com for the refund as a solution to their issues. Consumers are not pleased with Discounts and Special Offers and Diversity of Products or Services. The price level of this organization is high according to consumer reviews.They charged my debit card without authorization and continuously stated that it was 100% free, regardless of how I searched. This was unprofessional. I was very disappointed in every site I went to, stating that it was free.They took money in m’y bank account when.im.not on this site since febuary,i canceld and they took 47.90$ I wanna talk to.someone but when i call number not Unauthorized money taken out of my account It’s a $1.99 for one day drive I paid it you all took $5.99 out of my account two times and then took a extra $23.31 out of my account this is outrageous I did not ask for that I want my money back in Updated by user Jan 21, 2024

You can just take money out of those people’s account without them giving you permission to I want my money back I was only supposed to send me one dollar 99 cent no more no less I want my money thank you Original review Jan 21, 2024 False promotion you made me pay $36 for something that I thought I was paying $99 sent for for one day I did not want it for longer than one day I was just being curious and you stole everything in my account and I want it back thank you for understanding and putting my belongings back to the rightful beneficiary I’m trying to Deactivate this account. Every number you call is not on service. That tells a person automatically this is a *** company. Good thing I didn’t pay. Nonetheless, Unsubscribe me, Deactivate/Disqualify my account at once! Crazy part is, they know exactly what they’re doing! Pretending not to pay a person any mind. Don’t send me any emails, text messages, etc. Except to communicate that my account is done for. Thank you for your anticipated cooperation. You Bums! Preferred solution: Deactivate/Delete/Disqualify my account and picture. Do not use my private information at all. User’s recommendation: Don’t activate anything on this fake, fony and complicated site app. They charged my debit card without authorization and continuously stated that it was 100% free, regardless of how I searched. This was unprofessional. I was very disappointed in every site I went to, stating that it was free.This company is a scam they told me to pay $199 for a one-day pass and they charged me $5.99 two times and 23.31 time that’s $35 you cannot take money out of people’s account without telling them I ag I would like for my whole refund to be put back into my cash app account y’all had no reason and no business taking $35 out of my account and I only subscribe for $1.99 y’all took $5.99 out of my account two times in $23.31 out of my account once this is uncalled for and unnecessary and it is bad promotion please return my property back to the rightful beneficiary thank you Attempting to debit me after several messages that i dont have knowledge about the platform

May 24, 2024 I lost my cross bag containing my phone, ATM card and some valid ID card about two months ago or there about. When I eventually find it, I discovered that flirttender.com has been making attempt to debit me. I sent severally messages that I don’t know what the platform is all about neither do I have knowledge about it but to no avail. This debit attempt is getting much and I will like you to unsubscribe me or remove my bank information from your platform and please stop the attempt of debiting me. I never initiated this and I don’t know who use my Information for that purpose. Please, kindly do something to stop this. Kindly find the account details; 535522****694369 Moses Oyinloye Chatting but no actions . Stay away. ,…andmd….h&huhhhhhygfffdddfcfdffcffddrdddzddddxddddr c d dr Pros Too much chat with paid texters

Cons: Too much chat with paid texters Preferred solution: Full refund My teenage son, I got my card and used it on this site.I called him and asked him to please.Uh, refund me my money and to take my card off of this site.They did, and now they’re trying to charge my card again.For a monthly fee This site needs to be shut down and the police need to be involved in this this is ridiculous. This site is a scam I am being charged every month since I have used Flirty.com a couple of months ago. All I was paying for were credits to chat with other customers.I never knew that they were going to charge me a monthly service. What is the service for? All I needed were credits to use their services. So why are they charging me $12.99 a month? I’m not getting any credits for it. If that’s not included, then what is the $12.99 monthly charge for? I tried to call them today, and the phone number 888-884-**** is no longer in service. How can I get my credit card company to stop paying for this monthly charge that I didn’t sign up for? Preferred solution: I want my subscription cancel asap. I have no money in my account, but they are still allowed to charge me ? I have been trying to cancel the prescription for this site for 4 days the number that they give me the 884 **** does not work I’ve been trying to cancel it either saying you’re going to keep billing me I want to cancel the subscription but it just will not allow me to cancel it I talked to a consumer representative they said they were going to cancel it but they said they were going to give me a free month I said I didn’t need it but they said it’s free just use it we’re sorry about the inconvenience now I can’t I’m getting billed again for it I need to cancel this thing I’m not going to keep paying you guys man I’m not going to do it Needed to talk about £250 withdrawn from ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND, without my permission Took money without any explanation and I sent you an email that I wanted to cancel everything with you please cancel everything and delete my account I sent an email two days ago that I wanted to cancel everything and some how today I woke up and saw that you took money from my bank account with my right I want you to cancel the transaction you took and cancel everything I have on your page because I wanted from the first day to cancel everything so play CANCEL EVERYTHING I DONT WANNA SEE ANYTHING TAKING FROM MY CARD FROM YOUR COMPANY OR ELSE I WILL MAKE TO TELL MY LAWYER SND MAKE SOMETHING FROM REAL PLEASEEEEE CANCEL EVERYTHING WITH MY ACCOUNT

fantastic points altogether, you just gained a new reader.

What would you recommend about your post that

you just made a few days in the past? Any sure?

Самые популярные коляски Tutis, для стильных семей, Лучшие цветовые решения от Tutis, универсальный вариант, правила использования коляски, что приобрести для удобства, Как не ошибиться с выбором между Tutis и другими марками, сравнительный анализ колясок, чтобы сохранить отличное состояние, правила использования коляски, рекомендации для родителей, Какие факторы учитывать при выборе коляски Tutis, Почему Tutis – марка будущего, новинки на рынке детских товаров, Tutis: элегантность и стиль, стильный аксессуар для пап, поддержка родителей в заботе о ребенке

tutis коляска 3 в 1 [url=https://kolyaskatutis.ru/]tutis коляска 3 в 1[/url] .

Do you have a spam problem on this site; I also am a blogger, and I was curious

about your situation; many of us have developed some nice methods and we are looking to

trade techniques with other folks, be sure to shoot me an email if interested.

Hi there, You have done an excellent job. I will certainly digg it and personally recommend to my friends. I am confident they will be benefited from this site.

After research a couple of of the weblog posts in your website now, and I really like your method of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark web site record and will likely be checking again soon. Pls try my website online as nicely and let me know what you think.

magnificent submit, very informative. I’m wondering why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You must proceed your writing. I’m sure, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

Почему плинтус теневой так популярен?

напольный теневой плинтус напольный теневой плинтус .

Хостинг в Беларуси бесплатно: лучший выбор для вашего сайта, преимущества и особенности.

Бесплатные хостинги в Беларуси: что выбрать?, гайд по выбору.

Выбор профессионалов: топ-3 хостинга в Беларуси бесплатно, плюсы и минусы.

Простой гайд: как перенести свой сайт на бесплатный хостинг в Беларуси, шаги и рекомендации.

SSL-сертификаты на бесплатных хостингах в Беларуси: важный момент, за и против.

DIY: с нуля до готового сайта на хостинге в Беларуси бесплатно, шаги и советы.

Биржа хостинга в Беларуси: преимущества и особенности, обзор и сравнение.

Хостинг серверов https://gerber-host.ru/ .

Самые популярные pin up татуировки, для яркого образа

pin u0 https://pinupbrazilnbfdrf.com/ .

Широчайший ассортимент военных товаров|Боевая техника от лучших производителей|Купите военную амуницию у нас|Армейские товары по выгодным ценам|Магазин для истинных военных|Только проверенные боевые товары|Боевая техника для суровых реалий|Купите все необходимое для военной службы|Оружие и снаряжение для любых задач|Снаряжение от лучших производителей|Снаряжение для профессионалов военного дела|Выбор профессионалов в военной отрасли|Армейский магазин с высоким уровнем сервиса|Специализированный магазин для профессионалов|Выбор профессионалов в военной сфере|Боевое снаряжение от ведущих брендов|Только качественные товары для службы в армии|Специализированный магазин для военных сотрудников|Качественные товары для военных целей|Выбирайте только надежные военные товары

інтернет магазин військового одягу інтернет магазин військового одягу .

You are my inhalation, I own few blogs and often run out from to brand.

Throughout the great pattern of things you get a B+ with regard to hard work. Exactly where you lost me personally was first in your particulars. You know, people say, the devil is in the details… And that could not be more true here. Having said that, allow me reveal to you just what exactly did work. Your article (parts of it) is highly engaging and this is most likely why I am taking an effort to comment. I do not make it a regular habit of doing that. Second, despite the fact that I can easily notice the jumps in reasoning you make, I am not necessarily confident of just how you seem to connect your details which make your final result. For the moment I will yield to your issue but trust in the near future you link your facts much better.

Today, I went to the beach front with my children. I found a sea shell and gave it to my 4 year old daughter and said “You can hear the ocean if you put this to your ear.” She put the shell to her ear and screamed. There was a hermit crab inside and it pinched her ear. She never wants to go back! LoL I know this is totally off topic but I had to tell someone!

Hello! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest authoring a blog article or vice-versa? My website discusses a lot of the same topics as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other. If you’re interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Terrific blog by the way!

Merely a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw great pattern. “Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not one bit simpler.” by Albert Einstein.

It’s a shame you don’t have a donate button! I’d definitely donate to this brilliant blog! I guess for now i’ll settle for book-marking and adding your RSS feed to my Google account. I look forward to brand new updates and will share this website with my Facebook group. Chat soon!

Секреты успешного получения лицензии на недвижимость|Ключевая информация о лицензии на недвижимость|Подробное руководство по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Успешные стратегии получения лицензии на недвижимость|Разберитесь в процессе получения лицензии на недвижимость|Получите профессиональную лицензию на недвижимость|Лицензия на недвижимость: важные аспекты|Шаг за шагом к лицензии на недвижимость|Как получить лицензию на недвижимость: советы экспертов|Инструкция по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Секреты профессиональной лицензии на недвижимость|Полезные советы по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Получите лицензию на недвижимость и станьте профессионалом|Топ советы по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Профессиональные советы по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Эффективные стратегии для успешного получения лицензии на недвижимость|Шаги к успешной лицензии на недвижимость|Инструкция по получению лицензии на недвижимость|Лицензия на недвижимость: ключ к успеху в индустрии недвижимости|Секреты успешного получения лицензии на недвижимость: что вам нужно знать|Простой путь к получению лицензии на недвижимость|Основные шаги к профессиональной лицензии на недвижимость|Получение лицензии на недвижимость для начинающих: советы от экспертов|Процесс получения лицензии на недвижимость: ключевые моменты|Эффективные советы по успешному получению лицензии на недвижимость|Сек

How do you get your real estate license in Florida https://realestatelicensehefrsgl.com/states/florida-real-estate-license/ .

I haven¦t checked in here for a while because I thought it was getting boring, but the last several posts are great quality so I guess I¦ll add you back to my daily bloglist. You deserve it my friend 🙂

What Is FitSpresso? The effective weight management formula FitSpresso is designed to inherently support weight loss. It is made using a synergistic blend of ingredients chosen especially for their metabolism-boosting and fat-burning features.

Currently it appears like Wordpress is the best blogging platform available right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

[url=https://muhammad-ali.com.az]muhammad ali casino[/url]

best boxer in the world Muhammad Ali

muhammad ali apk

Что нужно знать перед походом к стоматологу, изучить.

Что такое эндодонтия, профессиональный уход за зубами.

Как избежать боли при лечении зубов, ознакомиться.

Мифы о стоматологии, в которые верят все, эффективные советы стоматолога.

Секреты крепких и белоснежных зубов, советуем.

Как выбрать хорошего стоматолога, качественные методики стоматологии.

Как избежать неприятного запаха изо рта, ознакомиться.

наша стоматологія https://klinikasuchasnoistomatologii.vn.ua/ .

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

Узнайте всю правду о берцах зсу, происхождение, познакомьтесь с, значении, тайны, Берці зсу: символ силы, Берці зсу: сакральное оружие, погрузитесь, освойте, в суть, погляньте, вивчіть

бєрци зсу бєрци зсу .

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having problems locating it but, I’d like to send you an email.

I’ve got some suggestions for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it develop over time.

If some one wishes to be updated with most recent technologies therefore

he must be pay a visit this web page and be up to date everyday.

Seeking out stripe keepers from EU nations.

You can earn 50 to 500 euros each day.

If you need more information, reach out on Telegram @aceyx3.

I don’t even understand how I stopped up here, however I thought this put up was once good. I do not understand who you might be but certainly you’re going to a famous blogger if you happen to aren’t already 😉 Cheers!

I was studying some of your articles on this website and I conceive this web site is rattling informative! Keep posting.

An excellent platform! The user-friendly interface and rich variety of content make it my favorite.

Uzun zamand�r b�yle kapsaml� ve kaliteli bir siteye rastlamam��t�m. Harikas�n�z!

Thanks to your site, I’ve gained knowledge on many topics. Kudos to you, you are truly amazing!

certainly like your web-site however you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very troublesome to tell the reality nevertheless I’ll definitely come again again.

An excellent platform! The user-friendly interface and rich variety of content make it my favorite.

A fantastic resource! The content is both informative and entertaining. I definitely recommend it.

مزاج , شيشةمزاج هو علامة تجارية تتخصص في صناعة وتوريد الشيشة ومستلزماتها. تتميز علامة التجارية بتصميماتها المبتكرة والعصرية، وجودة منتجاتها العالية، وتجربة العملاء

Harika bir kaynak! İçerikler hem bilgilendirici hem de eğlenceli. Kesinlikle tavsiye ederim.kurtköy escort